Moby Duck & Ducie Island

Monday, 25 April 2011 Sub-titled ‘The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them,’ this is a great book. The foolish author foolishly get interested in the story of the container load of bath toys washed off the ship Ever Laurel by huge waves on 10 January 1992. The Ever Laurel was bound from Hong Kong to Tacoma, near Seattle on the US West Coast.

Sub-titled ‘The True Story of 28,800 Bath Toys Lost at Sea and of the Beachcombers, Oceanographers, Environmentalists, and Fools, including the Author, Who Went in Search of Them,’ this is a great book. The foolish author foolishly get interested in the story of the container load of bath toys washed off the ship Ever Laurel by huge waves on 10 January 1992. The Ever Laurel was bound from Hong Kong to Tacoma, near Seattle on the US West Coast.

The container broke open, the cartons fell apart and the 28,800 bath toys – 7,200 of them yellow ducks – floated off to the ongoing entertainment of all sorts of people. Pursuing the story of those Moby Ducks kept Donovan Hohn busy for years and by the end of his travels he’d chased them down along the coast of Alaska, where many of them washed ashore. He’s sailed out of Hawaii looking for the great Pacific Garbage Patch. He’s gone to Hong Kong and on into China to track down where those rubber duckies were originally created. Of course they’re plastic, not rubber at all.

▲ My March visit to China for the launch of the new Mini Countryman also featured lots of yellow ducks, they were floated out on to the ‘lake’ which I floated on to for my talk with a Chinese TV interviewer.

He also sails across the Pacific in a container ship to get the feel for big seas although, probably fortunately, he never encounts a freak Monsterwelle. Finally he sails north of North America checking fast-melting Arctic ice and pondering if some of those escaped ducks might have made it all the way to the Atlantic. Along the way readers will learn a lot about ducks, bath toys, plastic, floating garbage, flotsam and jetsam, monster waves, cargo ships, ocean currents, global warming, polar bears, Arctic exploration and lots more.

I had my own encounter with the great Pacific Garbage Patch when I visited Ducie Atoll back in 1998. The Ducie chapter which follows is from the never published book I wrote about the Pacific voyage I made from the coast of Chile via Easter Island, Pitcairn Island and lots of other interesting islands before ending up in Tahiti.

I had my own encounter with the great Pacific Garbage Patch when I visited Ducie Atoll back in 1998. The Ducie chapter which follows is from the never published book I wrote about the Pacific voyage I made from the coast of Chile via Easter Island, Pitcairn Island and lots of other interesting islands before ending up in Tahiti.

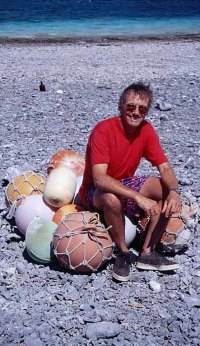

◄ Stray fishing floats I’d gathered together on Ducie in 1998

Ducie Island

‘It’s no wonder the crew are tense when we approach these islands,’ said Geoff.

The captain, dressed, as usual, in black, was striding nervously from one side of the bridge to the other. At the chart table I’d been studying British Admiralty chart number 987, which covers Ducie, Oeno, Henderson and Pitcairn islands. There was the odd note about an aerial survey by HMS Leander in 1937 and a tip of the hat to a US survey in 1941, but basically we were putting our trust in Captain F W Beechey, RNFRS and the good ship HMS Blossom, which passed this way in 1825 and 1826! Unfortunately Captain Beechey hadn’t had the time to do depth soundings for Ducie, we were coming in blind.

From this close Ducie was alternating strips of colour: the blue sea, then Acadia, the main island on the atoll reef, appearing as first a thin strip of white sand followed by an equally thin strip of green vegetation, then there was another strip of blue, the Ducie lagoon, followed by the same white, green, blue sequence on the other side of the atoll. This was a classic atoll, a squared-off oval reef about three km east to west and two km north to south. One side of the oval was closed off by Acadia while three smaller islets (motus as the Polynesians call them), one of them nothing more than a sand bank, were arrayed around the other half of the oval. There was no opening or ‘pass’ into the central lagoon, with tide changes the water just slopped in and out over the reef.

A classic atoll and a pretty basic one, the islands were not much over 100 metres wide and the vegetation was simple in the extreme, but although Ducie was uninhabited – by humans that is, there were lots of birds – its name certainly told a story. Lord Ducie had his name tagged on to this remote dot in the ocean by the notorious Captain Edward Edwards, who sailed by here in 1791 and named his discovery after his noble patron. Actually the island had already been discovered once before, the Portuguese explorer Quiros had come by in 1606 and named it Encarnacion. Still, Edwards had more on his mind than looking for previously discovered islands. He was carrying orders to round up Fletcher Christian and the rest of the villainous mob who’d made off with HMS Bounty two years earlier. Just over a year earlier, unbeknownst to Edwards, some of them, led by Christian, had settled on remote Pitcairn Island. Fortunately for Christian, Edwards may not have known about Ducie but he didn’t know about Pitcairn either. He sailed on west towards Tahiti, when taking a course just a few degrees south might have ended the Pitcairn saga before it really began.

It’s curious to contemplate what might have happened if Edwards had chanced upon Pitcairn island as well. Presumably he would have marched the mutineers off at gunpoint and today all four islands of the Pitcairn group would be uninhabited and would probably have become part of French Polynesia, just four more remote islands dribbling off the end of the Tuamotus group.

We edged in closer to the shore, dropping anchor in 110 metres of water, probably twice the ideal depth but who knows where the bottom suddenly reared up towards sea level? Somewhere between us and the beach lay the wreck of the Acadia, which went down here in 1881 and lies in just 10 metres of water. No lives were lost but it took the shipwrecked crew a nightmare 13 days to sail to Pitcairn Island. Philip Coffin, one of the sailors, must have taken his shipwreck as some sort of final message for he gave up the sea, settled down on Pitcairn, married 16 year old Mary Jane Warren (he was 44) and for many years Coffin was one of the most familiar Pitcairn family names.

We were picnicking on the lagoon side of the island, but first I wandered off eastward and almost immediately encountered the island’s famous litter problem. One of the most interesting research projects from the 1991-92 Sir Peter Scott Commemorative Expedition to the Pitcairn Islands was an investigation of the flotsam washed up on the beaches of Ducie and Oeno, and a comparison with what got washed up on Inch Island, a remote Atlantic coast Irish island. The conclusion? There’s a hell of a lot of stuff that gets washed up on even the most isolated stretch of coast and it’s pretty much the same whether you’re looking at an Irish island, close to population centres, or Pacific islands a very very long way away from anywhere.

In the survey Ducie and Oeno were notable for the huge number of fishing floats tossed up on the beach and the equally amazing number of whisky bottles. Particularly Suntory whisky bottles. When it came to bottles on the beach Suntory was the undisputed champion and as if to confirm the statistical integrity of the research the first bottle I picked up was, sure enough, a Suntory bottle. I also came across Johnny Walker bottles and Jack Daniels bottles but Suntory was way out front. Now do their bottles just last longer or do an awful lot of Japanese sailors slug back Suntory whisky and then nonchalantly toss the bottles overboard, to be washed up on pristine Pacific island coasts?

Fishing net floats were, if anything, even more abundant than bottles. They were littered along the beach in every size, shape, colour, material and configuration imaginable. I even saw an orange plastic one floating in while I was walking along the beach. There were silvery metal ones, foam ones, floats tied together in groups of two, three, four or more, big ones, small ones, even a couple of the glass ones which, these days, are quite valuable if undamaged. Late in the day I collected a cross section of float types to make a still life photograph. There was a walking trail across the island, delineated with driftwood, which we marked with my float collection. Will it still be there for future visitors? Remote though Ducie is and difficult as it is to anchor and visit, there had certainly been visitors before us, somebody had marked out the trail, Society Expeditions had left their memorial commemorating raising the Acadia’s anchor and down the far end of the island a bamboo flagpole marked a clearing which might have been a campsite.

Glass bottles and floats are far from the only trash scattered along the Ducie beaches. In between the plastic bottles, thongs, shoes, trays (including a batch labelled ‘Property of Feron Seafoods – Deposit Refundable’) there was also some really weird stuff. How had all those neon light tubes washed ashore without being smashed as they came over the reef? There was one big, black bin lid labelled ‘Not for Hot Ashes’, a single orange road works cone (how far away was the nearest road, let alone the nearest road being repaired?), an awful lot of rope (and not just wimpy amateur rope, this was the sort of rope you’d use to moor the QE2). And a single toy elephant.

Not everything washed up on the beach is modern. On the lagoon beach, the stretch along the inside of the island, there were a couple of iron ship’s stanchions; very old, rusted right through and flaking away. A bit further along was a cleat in similar condition. Both were far too heavy for one person to pick up. Now how had these washed up on the beach along with the plastic bottles? From the Acadia I speculated? Perhaps a large chunk of the wreck had been washed up, complete with stanchions, but in the subsequent century the wood had rotted away, leaving the iron bits to rust.

Of course beach was a pretty loose word to use for the Ducie coastline. Sure, there were stretches of that sandy stuff, but most of the Ducie coast was coral debris. An awful lot of coral debris. As I marched along the lagoonside beach I met Paul-the-rock, coming across from the other side of the narrow island.

‘The whole thing is completely covered with smashed up coral,’ he reported.

‘I’ve crossed over the island in two or three other places,’ he went on, ‘and there’s no soil at all. There’s nothing except broken and crushed coral.’

‘All this vegetation,’ he waved at the stand of scrubby bush-like trees, ‘ is growing straight out of that coral rubble.’

‘So what does that prove?’ I asked.

‘Well the highest point is only two or three metres high and the island is admittedly only 100 or so metres wide but there have been waves which have washed right across this island in the very recent past,’ he went on.

‘It must have been quite a storm,’ I said. ‘When do you reckon it happened,’ I continued, ‘in the last year or two?’

‘Oh no,’ Paul responded, ‘when I say very recently I mean sometime in the last century or two.’

I made a mental note to remember that geologists have a different appreciation of the word ‘very recent’ to us less Methuselah-minded individuals.

Inhospitable though the island may be, covered in broken coral and with no soil to speak of, it was still cloaked in dense vegetation although strictly of one type, the low bush-like tree known as beach heliotrope. Supposedly the island has a second, but closely related, plant but we didn’t see it. We did see lots of birds. They were around the boat as soon as dawn broke and when we were onshore they were remarkably fearless, clearly totally unused to human intruders. Along the beach to vegetation borderline were the big masked boobies, sitting on ‘nests’ which were nothing more than slight depressions in the coral debris. Back in the bushes were petrels of a variety of types but most often the Murphy’s petrels which are said to number 250,000. Fairy terns, snowy white and delicately beautiful, swooped and swirled above us. Early in the afternoon a group of red-tailed tropic birds, also snowy white but larger and with their long, thin, red tail showily elegant, soared overhead. On the seaward side petrels skittered across the waves, seeming to just skim the surface of the water with first one wingtip then the other. Up above there was the odd frigate bird, out on a mugging run, and just before we packed up to leave a single petrel floated right above our group, stationary on the wind blowing across the lagoon and only a metre or so above our heads. There was a steady breeze whisking across the lagoon and a constant throng of birds wavered back and forth above the island, the petrels periodically lowering their legs and spreading their webbed feet like air brakes.

In contrast to the busy birdlife and the exotic variety of trash deposited along the beach the lagoon life below sea level was very disappointing. Perhaps it was a factor of the limited inflow and outflow of water to the virtually closed off lagoon but the coral was dull and there were very few fish.

Strolling along the lagoonside after lunch I did, however, find one of Ducie’s famous whirlpools. Tunnels lead from the lagoon right out to the sea and water whirls in and out through these passages as the tide changes. It wasn’t much more than bathtub size and the whirl was a very gentle one but there was more variety of fish in that one little micro-zone than I’d seen in the rest of the lagoon.

Continuing along the lagoon edge, I found Art, sitting by himself, well away from the group, gazing across the lagoon to the islands on the other side of the atoll.

‘I was stationed on an atoll, like this but bigger, during the war,’ he told me. ‘The Cocos and Keeling Islands.’

‘It was incredibly beautiful and, you know, I thought I’d never seen anything like that again. And here I am.’

It was beautiful, perhaps because it was so minimised, so two-dimensional; there was no height to it, just thin strips of blue-white-green and then blue-white-green again and even that was absolutely simplified. The green was just one plant type, the birds were strictly limited. It was pure, simple and uncomplicated.

I was sweaty and salty as I clambered back up the stairs to the ship. ‘I’m heading straight for the shower,’ I reported.

‘Well make sure you conserve water,’ insisted the indefatigable Gretel, always ready to keep everybody on the ship toeing the line.

‘She ticked me off for smoking on the rear deck earlier this afternoon,’ reported David-the-room.

‘She announced that I risked blowing the ship up. I think she has decided the drums of lubricating oil are fuel.’

That evening in the bar there’s a recap of the Ducie visit and a briefing for tomorrow’s Henderson Island visit. Naturally Gretel has to ask an unanswerable question:

Gretel: ‘what was the name of that crab I saw?’

David-the-bird: ‘Henry.’

He’s not the only one suffering from Gretel-overload. Just after we arrived back on board I overheard Pam deliberately having a go at her, insisting she saw her sleeping on the beach despite her insistence that she just had her eyes closed. I’m beginning to suspect Pam might be good at this, she plays the slightly eccentric grey-haired English lady so well you overlook the cutting edge beneath it. Only a day or two out she crossed swords, pleasingly successfully, with Ben.

Pam: ‘Bennie …’

Ben: ‘Don’t call me Bennie, it’s Ben.’

Pam: ‘But when you introduced yourself you said your name was Bennie?’

Ben: ‘No I didn’t, would you like it if I called you Pammie?’

Pam: ‘Pammie is fine by me, Bennie.’

Bennie: ‘Grrr.’