Latest Posts:

Greenland – better go there soon

Wednesday, 28 January 2026

There are lots of places still to visit on my travel bucket list and Greenland is certainly one of them. In recent weeks Taco Trump has emphasised that it could be important to get there sooner rather than later. After all if Trump succeeds in invading Greenland we could find a visit to Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, would be rather like visiting Minneapolis in the US state of Minnesota. You could end up being shot and killed by ICE thugs sent in by Trump. A year ago I posted a blog – I’m Not Going There Anymore – about assorted places I should be avoiding, like the USA.

▲ you don’t want to meet these sort of people in the USA, the unmasked thug in the centre is Trump’s man Gregory Bovino and yes he does indeed look like Lockjaw, the villain in the movie One Battle after Another. And yes, that is his ‘Nazi cosplay coat’ or, as California Governor Gavin Newsom puts it, it’s a coat that’s ‘Nazi-coded.’

▲ you don’t want to meet these sort of people in the USA, the unmasked thug in the centre is Trump’s man Gregory Bovino and yes he does indeed look like Lockjaw, the villain in the movie One Battle after Another. And yes, that is his ‘Nazi cosplay coat’ or, as California Governor Gavin Newsom puts it, it’s a coat that’s ‘Nazi-coded.’

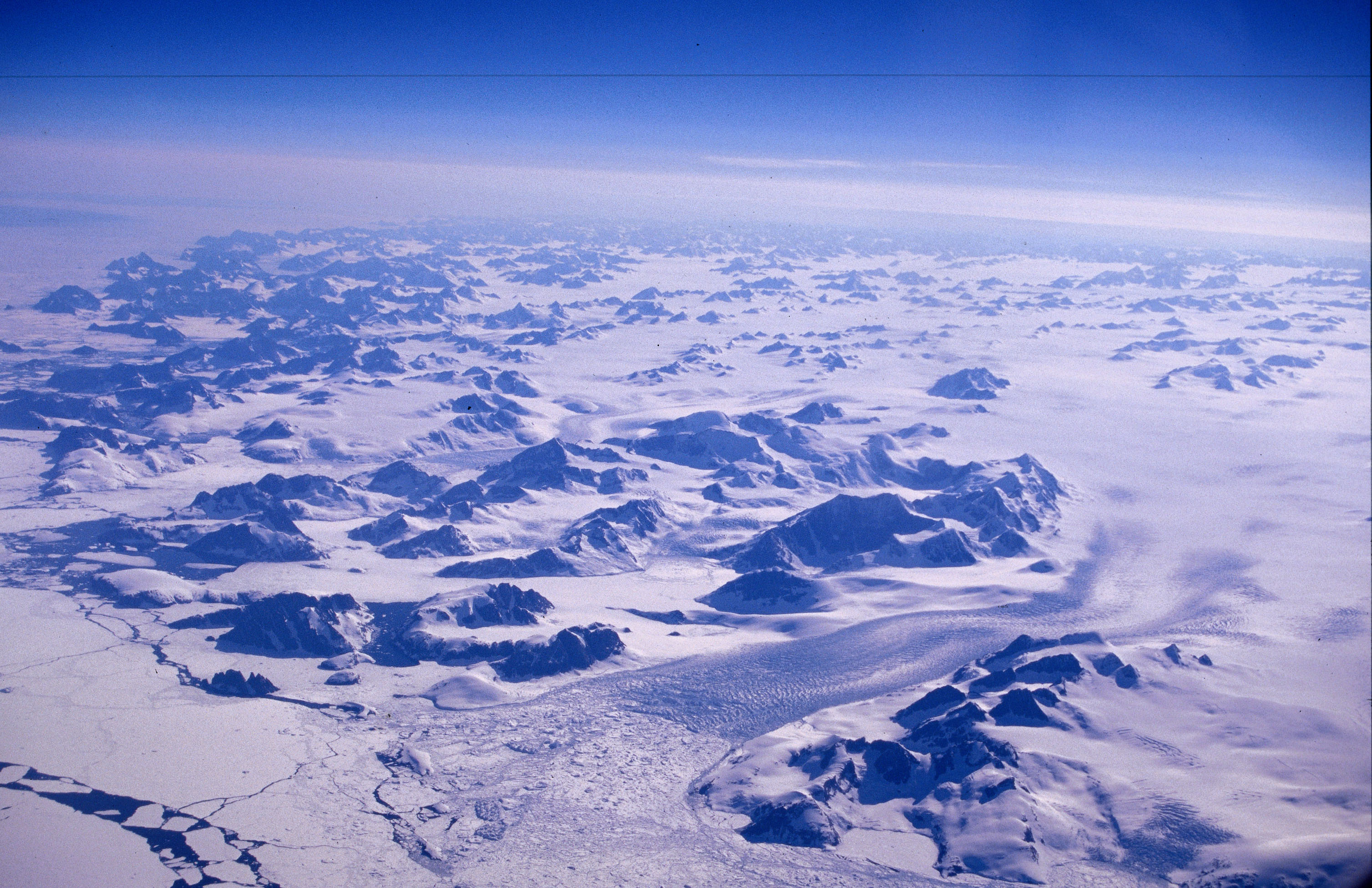

▲ Although I’ve never been to Greenland at surface level I’ve certainly flown over it numerous times and it’s always spectacular. Flying between Northern Europe and the West Coast of North America – London to Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles for example – the routing takes you way north over Greenland, northern Canada, Hudson Bay. It’s always a spectacular flight.

▲ Although I’ve never been to Greenland at surface level I’ve certainly flown over it numerous times and it’s always spectacular. Flying between Northern Europe and the West Coast of North America – London to Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles for example – the routing takes you way north over Greenland, northern Canada, Hudson Bay. It’s always a spectacular flight.

▲ Another Greenland view

▲ Another Greenland view

At surface level I’ve been to assorted northern destinations not unrelated to Greenland. Head east from southern Greenland and you could encounter Iceland or the Faroe Islands. Trump, whose geography expertise is not too good, tends to get Greenland and Iceland mixed up. And the Faroes are also Danish property, so watch out, Trump might decide he’d like to grab them too. Head east from northern Greenland and you’ll come to Svalbard, but that’s part of Norway, another place that tends to confuse Mr Trump. Further south I managed to reach L’Anse aux Meadows at the north-western tip of Newfoundland, that was a Viking outstation for Greenland when the Vikings – rather than the Danes – ran the place.

▲ I have been to the Wolfe Creek Meteorite Crater in Australia, flown over and driven to it along the Tanami Track from Alice Springs. If you’d like a bucket list of other amazing meteorite craters check Sites of Impact.

▲ I have been to the Wolfe Creek Meteorite Crater in Australia, flown over and driven to it along the Tanami Track from Alice Springs. If you’d like a bucket list of other amazing meteorite craters check Sites of Impact.

▲ The 10 craters it covers includes the New Quebec (aka the Pingualuit or Chubb Crater), a long way from anywhere in Canada, handily placed between Hudson Bay and Greenland. (image of the Pingualuit Crater from Wikimedia)

Tags

▲ you don’t want to meet these sort of people in the USA, the unmasked thug in the centre is Trump’s man Gregory Bovino and yes he does indeed look like Lockjaw, the villain in the movie One Battle after Another. And yes, that is his ‘Nazi cosplay coat’ or, as California Governor Gavin Newsom puts it, it’s a coat that’s ‘Nazi-coded.’

▲ you don’t want to meet these sort of people in the USA, the unmasked thug in the centre is Trump’s man Gregory Bovino and yes he does indeed look like Lockjaw, the villain in the movie One Battle after Another. And yes, that is his ‘Nazi cosplay coat’ or, as California Governor Gavin Newsom puts it, it’s a coat that’s ‘Nazi-coded.’ ▲ Although I’ve never been to Greenland at surface level I’ve certainly flown over it numerous times and it’s always spectacular. Flying between Northern Europe and the West Coast of North America – London to Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles for example – the routing takes you way north over Greenland, northern Canada, Hudson Bay. It’s always a spectacular flight.

▲ Although I’ve never been to Greenland at surface level I’ve certainly flown over it numerous times and it’s always spectacular. Flying between Northern Europe and the West Coast of North America – London to Vancouver, Seattle, San Francisco or Los Angeles for example – the routing takes you way north over Greenland, northern Canada, Hudson Bay. It’s always a spectacular flight. ▲ I have been to the Wolfe Creek Meteorite Crater in Australia, flown over and driven to it along the Tanami Track from Alice Springs. If you’d like a bucket list of other amazing meteorite craters check

▲ I have been to the Wolfe Creek Meteorite Crater in Australia, flown over and driven to it along the Tanami Track from Alice Springs. If you’d like a bucket list of other amazing meteorite craters check